Research

The over-arching question of my research is: How does the evolution of form and function contribute to the accumulation and maintenance of biodiversity?

I approach this question in a variety of ways, focusing mostly on the diversity of fish feeding mechanisms. My work includes videography of live fishes, large-scale morphological datasets of museum specimens, and development of phylogenetic comparative methods for better leveraging the data we have about organisms into the methods we use to model their evolution. To do this work, I integrate functional morphological studies of live animals, typically in the lab, with museum specimens and statistical models of evolution.

I approach this question in a variety of ways, focusing mostly on the diversity of fish feeding mechanisms. My work includes videography of live fishes, large-scale morphological datasets of museum specimens, and development of phylogenetic comparative methods for better leveraging the data we have about organisms into the methods we use to model their evolution. To do this work, I integrate functional morphological studies of live animals, typically in the lab, with museum specimens and statistical models of evolution.

Major research themes

I. How do fishes modify their feeding apparatus to capture prey with diverse mechanical properties? Nearly all fishes are capable of using suction feeding for prey capture. Suction is a dynamic feeding mechanism that relies on rapid expansion of the head, and the density and viscosity of water, to pull in water and a prey item. Yet there are many common prey, such as algae, corals, and sponges, that are attached to the substrate and not easily captured with suction. Many fishes have evolved a novel feeding mode, which we refer to as “biting,” to scrape, graze, or yank these prey directly form the substrate. Biting is a wholly different functional process than suction: where suction relies on expansion of the jaws, biting relies on compression and force transmission directly through the jaw apparatus. This novelty is an opportunity to ask a range of questions about the adaptive evolution of novelty, how fishes can modify an existing feeding apparatus to capture different prey, and more.

I. How do fishes modify their feeding apparatus to capture prey with diverse mechanical properties? Nearly all fishes are capable of using suction feeding for prey capture. Suction is a dynamic feeding mechanism that relies on rapid expansion of the head, and the density and viscosity of water, to pull in water and a prey item. Yet there are many common prey, such as algae, corals, and sponges, that are attached to the substrate and not easily captured with suction. Many fishes have evolved a novel feeding mode, which we refer to as “biting,” to scrape, graze, or yank these prey directly form the substrate. Biting is a wholly different functional process than suction: where suction relies on expansion of the jaws, biting relies on compression and force transmission directly through the jaw apparatus. This novelty is an opportunity to ask a range of questions about the adaptive evolution of novelty, how fishes can modify an existing feeding apparatus to capture different prey, and more.

III. How have functional innovations contributed to the accumulation of diversity among fishes? It is easy to imagine that a functional innovation that allows access to a novel ecological niche could result in an increase in phenotypic or species diversity. Yet that is not always the case: the slingjaw wrasse, Epibulus, has one of the most innovative jaw mechanisms in the fish world and can extend its jaws 65% of the length of its head, yet has only two species and both use the mechanism identically (image, left). What are the features of innovations that promote subsequent diversification? Why do some innovations appear repeatedly, like biting, and others sparsely, like the extended jaw apparatus of slingjaw wrasses?

III. How have functional innovations contributed to the accumulation of diversity among fishes? It is easy to imagine that a functional innovation that allows access to a novel ecological niche could result in an increase in phenotypic or species diversity. Yet that is not always the case: the slingjaw wrasse, Epibulus, has one of the most innovative jaw mechanisms in the fish world and can extend its jaws 65% of the length of its head, yet has only two species and both use the mechanism identically (image, left). What are the features of innovations that promote subsequent diversification? Why do some innovations appear repeatedly, like biting, and others sparsely, like the extended jaw apparatus of slingjaw wrasses?

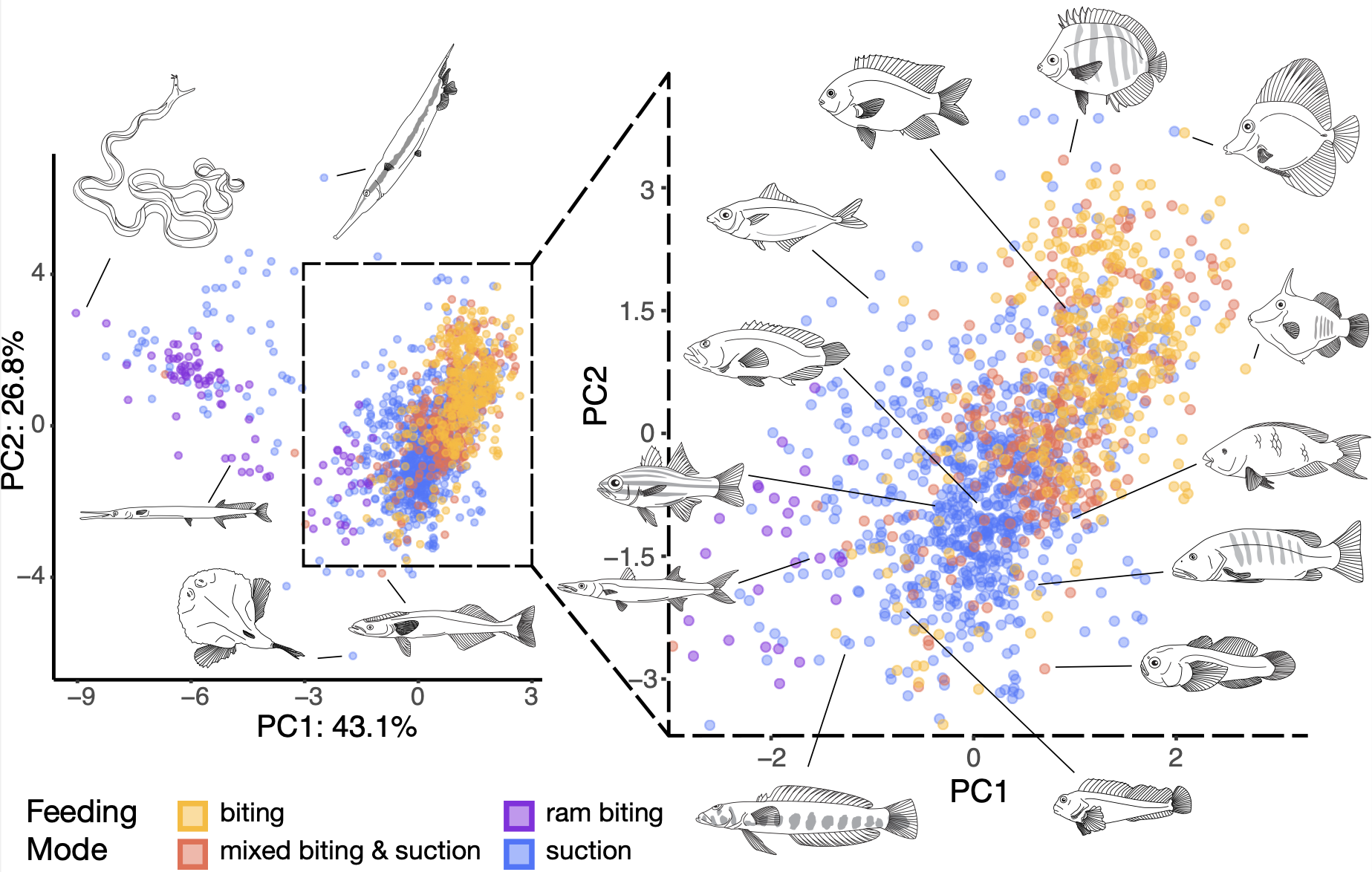

IV. How does historical contingency shape the differences in parallel radiations? Radiations in closely related groups of fishes, like cichlids, are an opportunity to see how groups with shared ancestry may accumulate different functional and morphological diversity (reef fishes' body shape diversity, left). For example, Neotropical cichlids include such bizarre fishes as the extremely laterally-compressed Discus for which there is no comparable morphological analogue in African cichlids, but African Great Lake cichlids have accumulated comparable diversity in feeding kinematics to Neotropical cichlids in just a fraction of the time. What is different about the conditions in which each lineage has evolved that have led to such different processes of accumulating diversity? Which is more typical of the accumulation of phenotypic diversity across vertebrates? These and other questions fascinate me.

IV. How does historical contingency shape the differences in parallel radiations? Radiations in closely related groups of fishes, like cichlids, are an opportunity to see how groups with shared ancestry may accumulate different functional and morphological diversity (reef fishes' body shape diversity, left). For example, Neotropical cichlids include such bizarre fishes as the extremely laterally-compressed Discus for which there is no comparable morphological analogue in African cichlids, but African Great Lake cichlids have accumulated comparable diversity in feeding kinematics to Neotropical cichlids in just a fraction of the time. What is different about the conditions in which each lineage has evolved that have led to such different processes of accumulating diversity? Which is more typical of the accumulation of phenotypic diversity across vertebrates? These and other questions fascinate me.

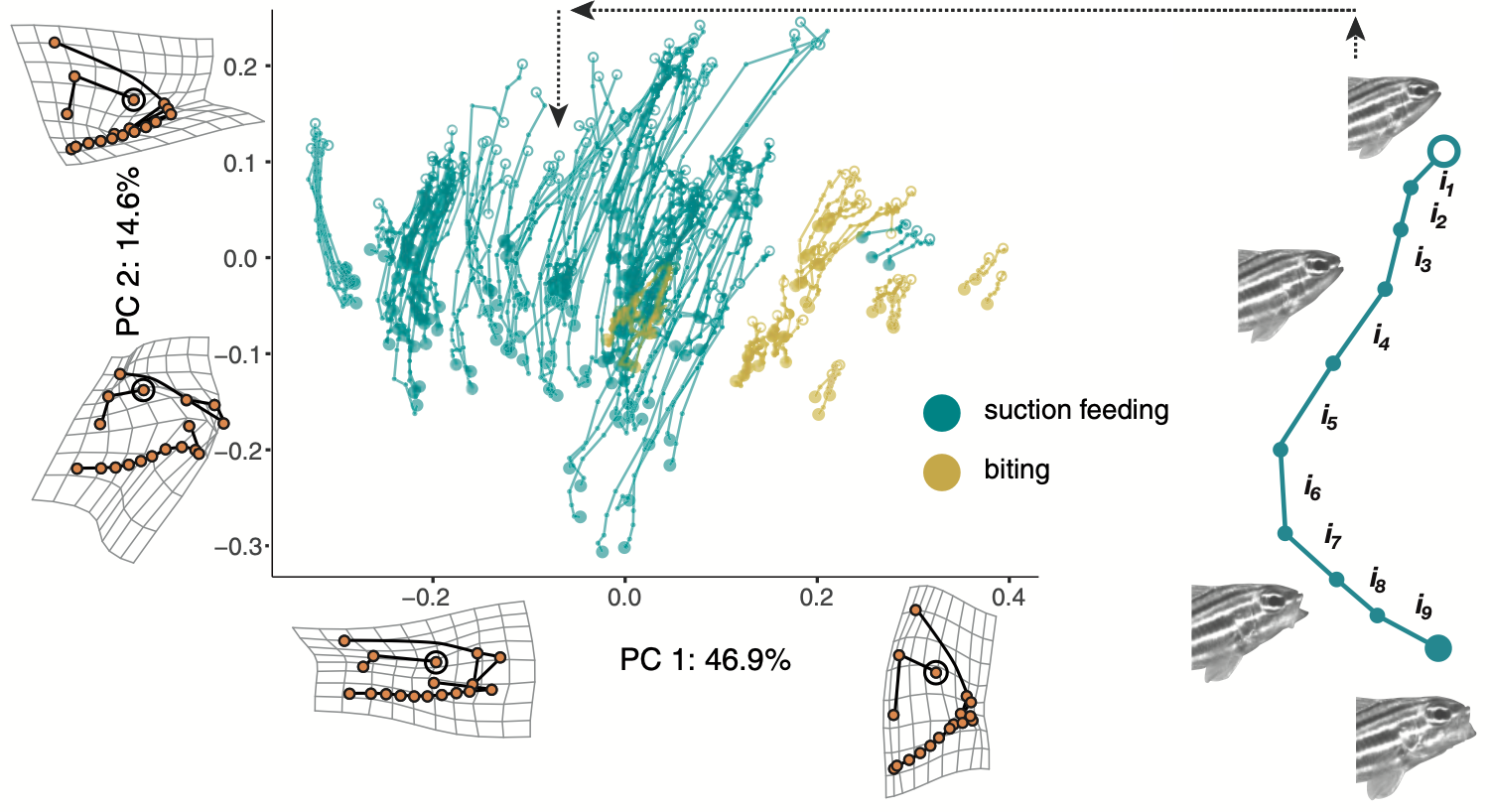

V. How can we leverage performance landscapes to understand macroevolution? It is common in the study of macroevolution to fit models, like Ornstein-Uhlenbeck models, that estimate the rate of evolution of a trait and the ‘optimum,’ or ‘adaptive peak,’ for that trait, towards which lineages are evolving. These models simultaneously estimate rate of evolution towards the peak and the location of the peak in phenotypic space. But we have more information that the implementation of that model would suggest! Using hydrodynamic simulations, the Holzman and Martin labs have estimated the shape of the performance landscape itself. In my current research with Josef Uyeda, we are building models that take advantage of our existing knowledge about the shape of the performance landscape to better estimate the dynamics of adaptive evolution of suction feeding.

V. How can we leverage performance landscapes to understand macroevolution? It is common in the study of macroevolution to fit models, like Ornstein-Uhlenbeck models, that estimate the rate of evolution of a trait and the ‘optimum,’ or ‘adaptive peak,’ for that trait, towards which lineages are evolving. These models simultaneously estimate rate of evolution towards the peak and the location of the peak in phenotypic space. But we have more information that the implementation of that model would suggest! Using hydrodynamic simulations, the Holzman and Martin labs have estimated the shape of the performance landscape itself. In my current research with Josef Uyeda, we are building models that take advantage of our existing knowledge about the shape of the performance landscape to better estimate the dynamics of adaptive evolution of suction feeding.

Funding

I am very grateful to the many organizations that have supported my research on these topics, including the National Science Foundation, the American Association of University Women, the Achievement Rewards for College Scientists Foundation, UC Davis, the UC Davis Center for Population Biology, Cornell University, Friday Harbor Marine Laboratories, the Stephen and Ruth Wainwright Endowment Fund, and the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology.